An off-ramp from the road to dystopia

The Learning by Doing project (LbD) looks at possible development pathways and asks its participants to first imagine a future as they’d like it—always within a 2-1.5˚ emission and adaptation scenario—and also a future that they’d consider dystopian. From these elements, the project has considered possible future visions of a desirable world, and a narrative towards them, as a guideline for metric and non-metric markers towards a “good life” within the envelope of the Paris Agreement.

At our most recent cross-project meeting, occurring on Thursday 8 December, participants received a rundown of project advances and insights. In particular, the Latin America region’s report to the meeting highlighted the discrepancy between current growth trajectories in Latin America, and social development on the ground—which resulted in an interesting insight given the context of the project.

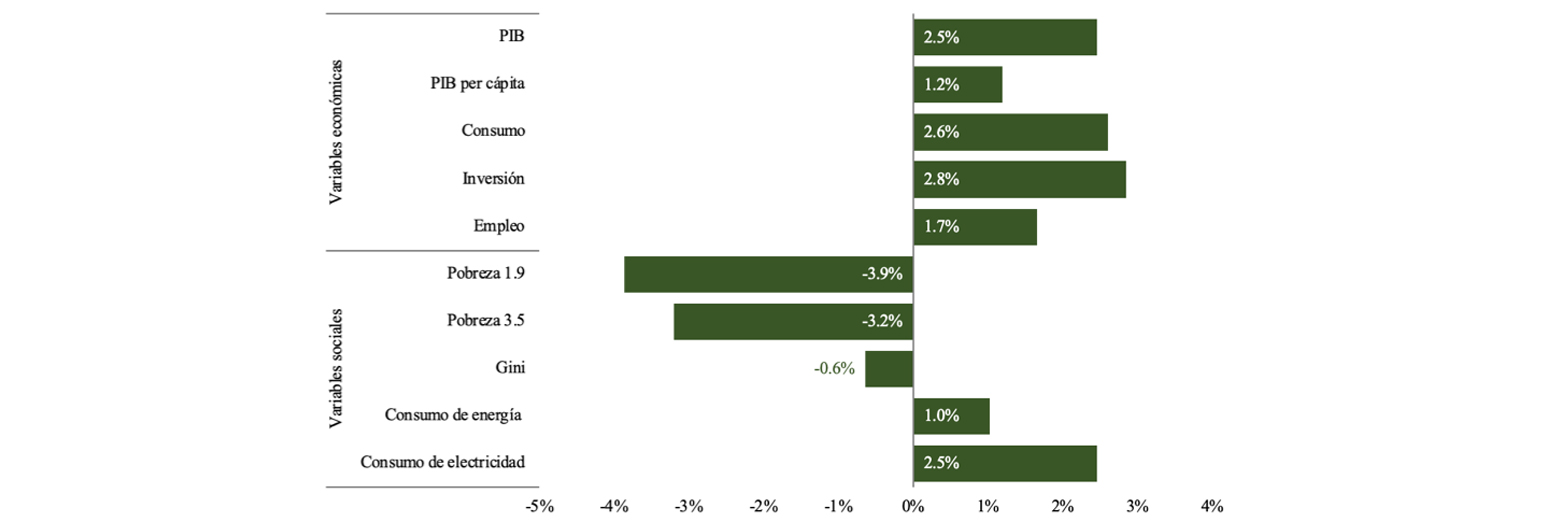

The report highlighted that regional PIB (GDP in English) and other positive indicators moving briskly, but because of the worsening of an already-poor Gini coefficient, poverty is not being reduced in accordance with our Sustainable Development Goals—employment and investment is benefitting an ever smaller proportion of the population. This does not bode well as a picture of social sustainability.

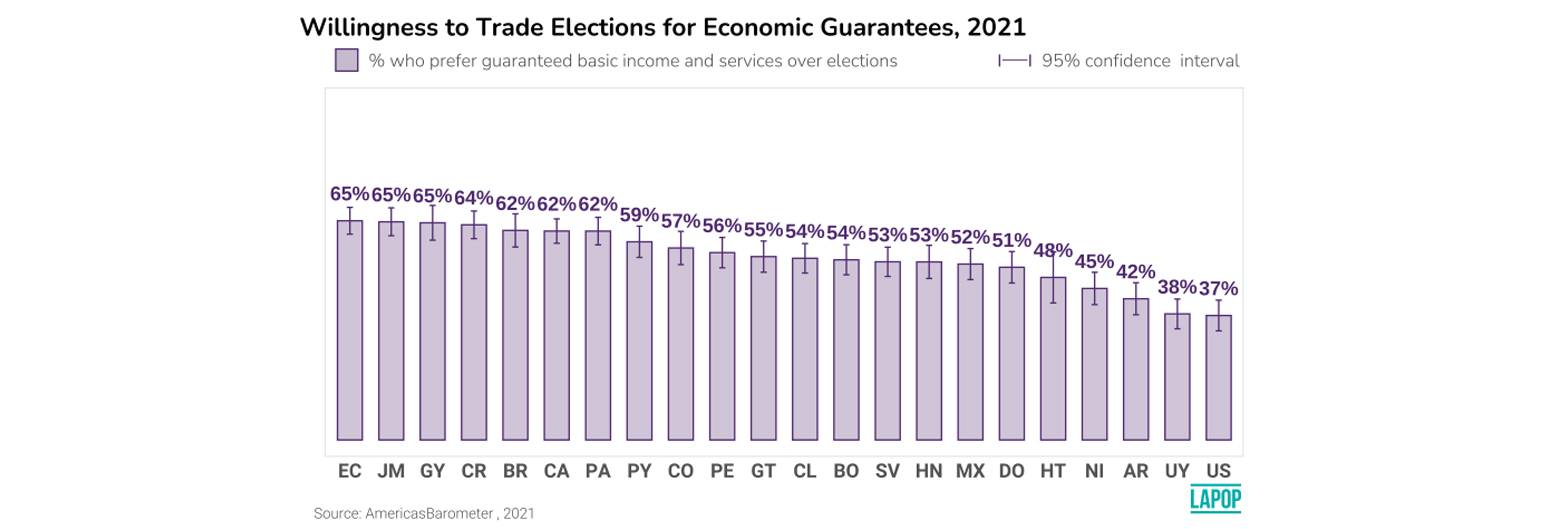

Collaterally, and independently of our Latin American discussion in LbD, and as an independent check on the above observation, the 2021 Americas Barometer survey describes that more than half the countries of Latin America are willing to trade their political freedom for basic income and services.[1] Given the general demographic of the region, this suggests that this opinion is favoured by younger people, who may perhaps not have the memory of the region’s earlier experience with autocracy. If we exclude the US, more than 50% of adults in 17 out of 21 countries prefer a system that delivers economic guarantees over one that guarantees orderly transitions.

This may be reinforced in the region by a movement towards more authoritarian, “big government” initiatives in the region, as noted from Mexico to Brazil over the past few years, and risks to social development that may follow.

Current policies in Latin America are perhaps not delivering a “good life” to enough people. Discontent in many capitals has been notable since before the pandemic—so the austerity associated with the pandemic isn’t the cause—incumbent presidents and their parties have lost the last 15 elections in Latin America.

LbD’s focus on alignment of climate investment towards not just carbon emissions targets, but bundling these aims with developmental pathways looking to address real needs and desires of a society, looks to make the most out of the socio-economic transformation that climate change is forcing on all of us.

If current trends in development in Latin America are moving its people towards a dystopian future, with real economic data and experiences of social unrest and division across the continent painting an ever-clearer picture of that, then LbD looks to signpost an off-ramp.

As has evolved in the project’s findings, climate-aware capital investments can be targeted to create disposable income across the economy by actively pursuing societal needs with climate and transition-aware projects, and not staying in an emissions-focused tunnel-vision. This follows the project’s philosophy of the importance of relevance and benefit of climate and transition projects at a social, and personal, level in order for the transition to a sustainable future to happen at the speed we require. Thus, LbD looks to use the important new investments required for a transition to Paris-aligned economies not only to deliver the mitigation and adaptation goals so important for climate challenges, but to also deliver disposable income away from energy and transport (for example), and towards health and education (for example), and a better quality of life across society.

If the Latin American region is faltering in its provision of inclusive prosperity, with governments finding difficulty in formulas that create broad benefits, a strategic move to dealing with emissions, development, industry, climate adaptation, and quality-of-life—what the project calls “Buen Vivir” within a 2-1.5˚ future—becomes clearer. LbD’s economic studies on the relevance and opportunities in considering domestic development in this way, alongside the added benefits of economic independence associated with advances in renewable energy, circular economies, and improved nature-based solutions, are illuminating important benefits for countries across the region.

As LbD now moves to a more implementation-centric phase in its forward-looking approach, with more concrete projects, policies, and case-ideas, we will be fleshing out the off-ramp from Latin American BAU. But at this stage, the signposting is clear.

Gilberto Arias

[1] See: https://www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/insights/IO953en-1.pdf