Principles of Common Pool Resources (CPR). 03 May, 2024

In CPR, resource management is discussed in search of adaptive management of goods that have open access; that is, any person could benefit from said good. Often, the good can cover a large area, and it is often not easy to demarcate its users—so the concept of “club” does not operate either.

In these circumstances, the way in which actors in public space develop the governance of their space is called “adaptive”; in this concept, as governance of the good moves away from the central justice system, management norms must be primarily beetween the users of the good, towards the conditions of use.

Ostrom’s Principles

Elinor Ostrom highlighted eight principles to govern CPR interests in an adaptive manner, where the agency and benefit of public goods governance lies with the participants of the good, rather than being governed by a central government.

- Governance of goods must be directed towards public goods in their own context, including functions in the management context.

- CPR governance must establish restrictions on the space of action; it is important to have a mechanism to include stakeholders and exclude peripheral actors without participation in the CPR regime.

- There must be agreements between CPR participants for decision-making opportunities in the management of the matter.

- CPR users must have a monitoring system, and such monitoring system must be transparent and timely for consultation and verification by all CPR users.

- The CPR must have a punitive system to impose restrictions or penalties to reinforce adherence to CPR norms and values.

- It is necessary to have a friendly and effective dispute resolution regime, which is low-cost, but normatively measured against abuse.

- It is important for the CPR regime to have some recognition in a higher legal framework, to avoid conflicts between the regime and the higher legal system, which could be used by non-affiliated actors to seek advantage of public goods managed within the CPR community.

LbD

Our goal in the LbD project is to articulate climate action—whether it be adaptation, mitigation, sustainable development, climate justice, or just transition—in terms of creating a good life, rather than measuring emissions.

To this end, we have studied transitions to futures in line with the Paris Agreement and adapted to the climate and impacts of a 1.5-2˚ hotter world. In our studies, we have seen evidence that managing the transition through carbon pricing is an economically and politically difficult task, with a high risk of ineffectiveness and inefficiency.

Instead, we have focused on patterns where actions work from the ground up, towards common goals that can be coordinated between sectors, seeing how sectors support each other towards those goals, and how actors within sectors can manage—within their own interest—towards goals that add up to the transition of the entire sector, and in turn to the entire economy, in a transition to a low-carbon economic system.

The vision of LbD does not rely on perfect market information—in fact, it assumes that markets or general regulation cannot remedy all failures in all cases—especially in cases of rapid development. In addition, LbD understands that there is a nature of caution, or inertia, in moving away from “trusted” practices, which may need to be displaced in the transition. However, it is clear that the transition to low-carbon economies is something that requires urgent attention, and it is also clear that there are material advantages to reaching that condition of a low-carbon economy promptly.

What LbD seeks, and delivers, is a methodology to create demand for such a transition, a demand not defined by, or entirely dependent on, governmental management, and manage the interests of actors in a sector towards the improvement of the sector—delivering a good life for the participants—and creating a clear target for climate change investment and management that not only meets the Paris Agreement goal but also tangibly delivers a better life for its citizens.

Integration with Ostrom

Guidance on principles and benefits is crucial.

In pursuit of the goal of generating interest among participants in a community to maximize the benefits of their management, LbD seeks to align these interests with those of sustainable development, towards a “good life” within each sector.

To this end, LbD seeks to identify actors within a sector whose functions are important for sectoral development in the expected manner – recognizing that no single actor can develop a sector in its entirety, as there are several different functions that must be addressed in each sector, and if initiatives that cover the entire sector at once are relied upon, this would imply “top-down” management, prioritizing the main, large actors. Instead, LbD seeks to create greater social impact in such projects, as will be highlighted.

LbD has found that bottom-up actions have a greater opportunity to find co-benefits, and to generate greater economic inclusion in development. This in turn facilitates both the political management of sustainable development programs, as well as broadening the demand for such programs.

If we can consider that, with support and knowledge, each actor in their sector knows best how to care for and develop their framework of action in a vision of sustainable development towards a “good life” in their sector, which has its own incentives in this regard, we can design sustainable development policy management that is aligned with the real economic and social development aspirations of the population.

“Packages” of Action

LbD does not seek to identify or correct externalities, but to develop a purpose alignment between actors in a sector and the sustainable development goals of their society. It works not only on the supply side—of technology solutions, projects, and such—but also on the demand side of such solutions. And this balance is aimed at “bottom-up” actions, visualized at the sub-sector level, but with a view to the purposes of the entire economy and in collaboration with the development of other sectors.

This approach has the advantage of trying to align both political and private purposes, following a co-management alignment in the style of Ostrom’s CPR frameworks.

This is achieved through “action packages” that first identify, then sensitize, and then train the creation of action CPRs – always with a view to creating a “good life” in sustainable development, in line not only with social goals, but also with ambitious NDCs according to the goals of the Paris Agreement, always towards adaptation in line with a climate of 1.5-2˚ of greater warming.

Our discussion below focuses on sub-sector implementation – which is the management of practice, the implementation of the action theory and its philosophy of “good life” as the development goal, rather than simply focusing on emissions indicators and such.

Progression

Visualization – orientation – training – facilitation

The progression we have developed, which follows a trajectory of socio-economic transition, begins first with a consideration—handled as a consultation—about the preferred development direction in a general sense, considering not only emissions and adaptation, but also a conception of a “good” future life.

- This visualization becomes an initial approach that can be subdivided into sectoral actions.

- Looking at the sectors, the functions and management of actors within each sector – which we would call sub-sectoral actors – are considered; CPRs of action are constructed based on these actors.

For these actors, we would address concepts similar to those identified by Ostrom in the organization of sub-sectoral actors, since our direction is to facilitate an ecosystem of actors who are motivated to create a “good life” with resources that the system develops within reach. As developed by Ostrom:

- The sub-sectoral space must be defined and the function of actors in the context of their development towards a “good life” must be clear;

- Action in the sub-sectoral space must be defined, emphasized, or facilitated for particular actors who will have an interest in the development of specific sub-sectoral functions;

- The evolution of the sub-sector must be dynamic, addressing obstacles and opportunities, with the inclusion of the opinions of sub-sectoral actors;

- Actors must include elements of monitoring of sub-sectoral management (this happens to be important in attention to MRV of actions, which is a necessary function for both climate action considerations and financial order);

- The sub-sectoral system needs an ordering system to ensure adherence to norms and purposes, inflections of practices, which the transition requires;[1] and

- It is necessary to have legal support on norms and practices – which may be conditions for certain legal benefits in sub-sector management – which would resemble a regime of benefits and conditions for participating and enjoying the benefits, and to protect the regime from abuse.

[1] If there is no clear way for participants to exit the CPR agreement due to mismanagement, then there must be some penalty regime so that the mismanagement of the resource does not go unpunished. It is clear that if there is an ability to exit the system, then the project would collapse in case of mismanagement, as its participants would leave; since this is not a clear option, there must be some concept of enforcement.

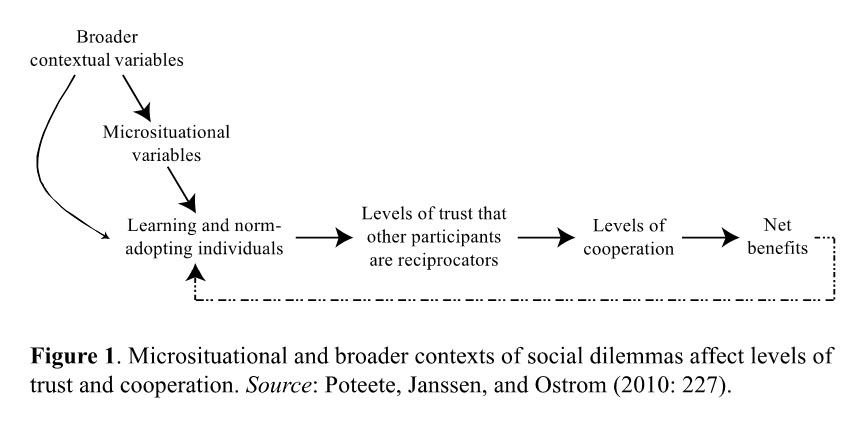

From a shared vision of what is wanted to be achieved – and what is wanted to be avoided – sub-sectoral initiatives would be developed (referred to as “Microsituational variables” in the following graph), which would function “bottom-up”, so that a larger part of the population could participate in the path of sustainable development, and that would understand it as something positive and their own, and not as a program imposed by third parties.

- A representative group of such sub-sectoral CPRs is offered guidance on the management of their functions, on the direction and benefits that could be achieved, and the responsibilities that come with acting in their sub-sector according to CPR principles[1]. It is also important to communicate the operating deadlines and the opportunities for adjustment that would be made over time.

It is important that the goals of the sub-sector be communicated to relevant actors, and that their concerns and comments be addressed; in particular, it is important that these actors understand the programmatic benefits – and the eventual expiration of such benefits – since the urgency of the transition is also important.

Moving from a period of orientation and familiarization, the next general stage is about addressing implementation barriers.

The first step is to facilitate a period of sub-sectoral CPR action management, so that the benefit of a “good life” can be felt, and so that the acceptance of transition of practices and technology becomes more functional. This exercise must also include the aforementioned training and monitoring management, and must begin to approximate the level of financial support needed in the transition of activities. The purpose of this step is to overcome the barriers of practices and inertia of BAU of our socio-economic systems.

The next step is to already develop the financial tools to achieve the mechanisms to facilitate the reach of new practices and technology on a large scale. It is important that such financial tools have a beginning and an end, as it is important to a) communicate urgency towards the transition (greater incentive for rapid action), and b) that such incentives do not become long-term subsidies, which would not be sustainable – therefore, facilitations (including for the financial sector itself) must have a progression towards an end.

It is possible that particular actions may need to have at least the threat of eventual penalty to achieve incentives for the inflections that are needed – eventually, it must be prohibited, except for rare exceptions, the dispatch of fossil fuels, which implies that eventually the importation of vehicles for these fuels should be prohibited, or the installation of new gasoline dispensers.

Other elements

Clearly, the development of these sub-sectorial initiatives would involve a commitment to a distributed and polycentric development, as well as opportunities for innovation in the economy. This would naturally involve a diversification of extractive industries, and a realignment of existing industries towards sustainability and adaptation.

In this case, the role of the higher education system cannot be underestimated, as it would seek an important role in the development of practices in various sectors, always tuned to local conditions and requirements, along with the dissemination of new production and management practices and methodologies.

Gilberto Arias, London, 2022

[1] Ostrom and others mention the importance of cooperative participants recognizing that they have “High Marginal Per Capita Return (MPCR)”, as when the per capita returns of cooperation are high, there are greater incentives to recognize the benefits of cooperative actions.